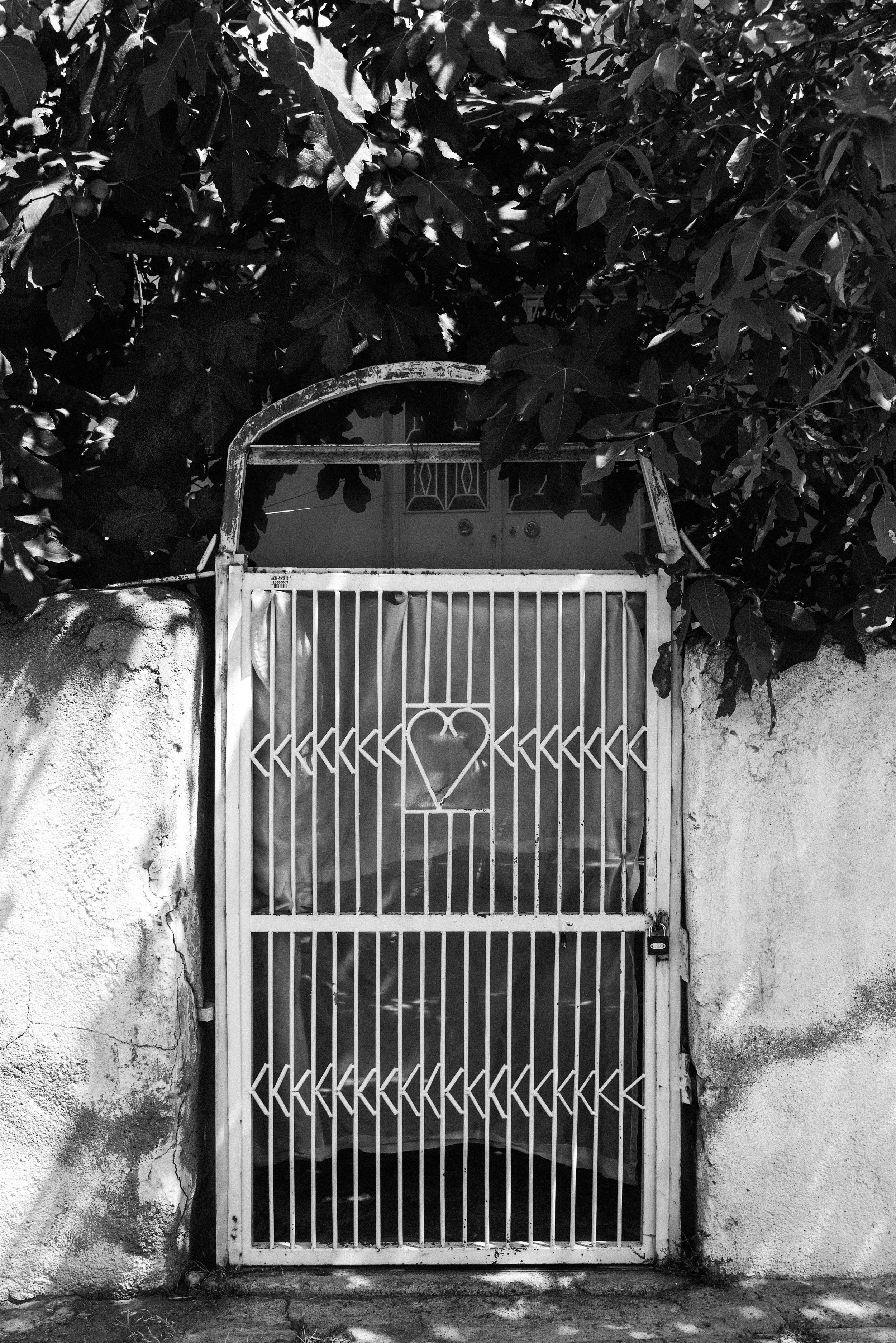

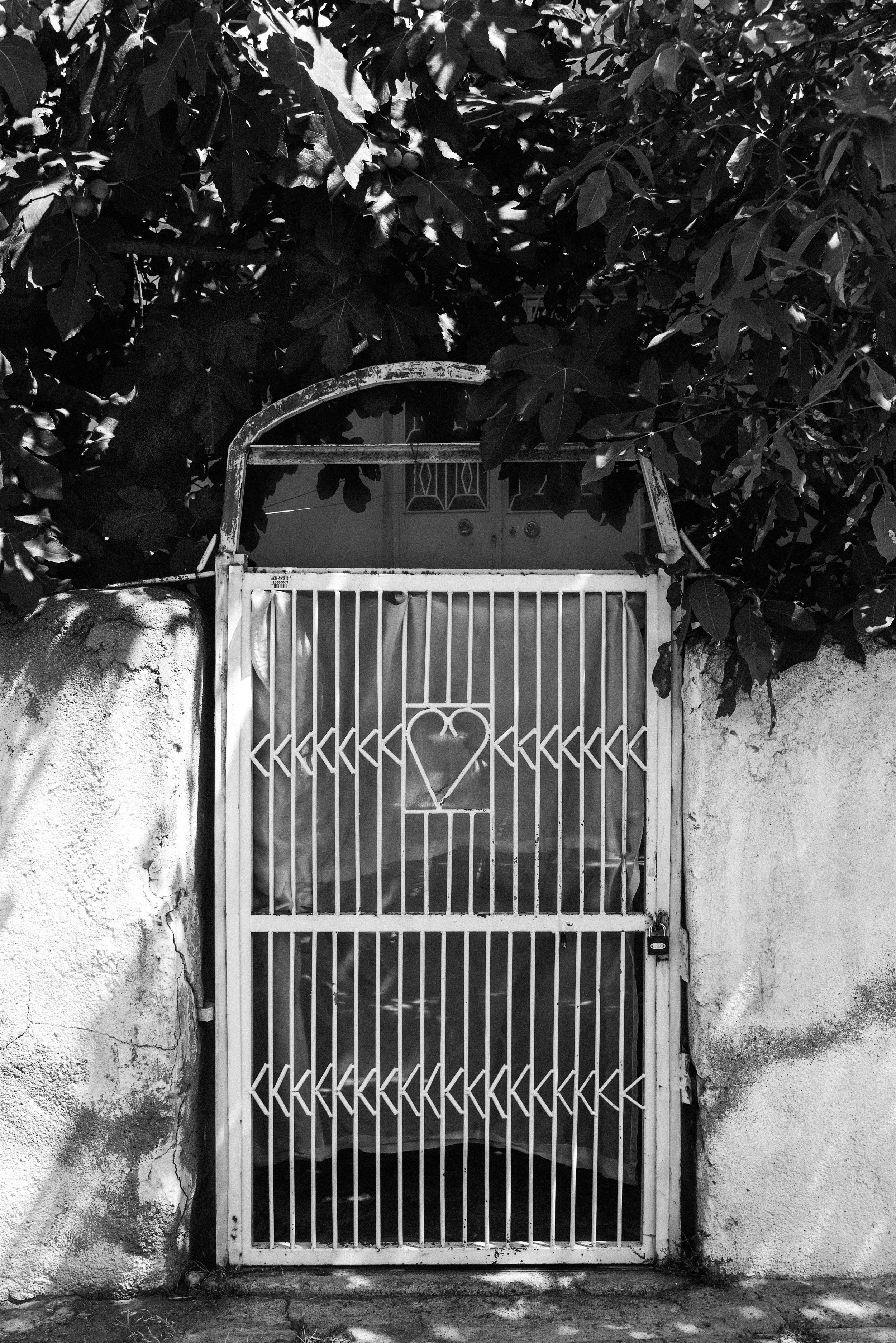

Right of Return

Forgotten by Time

Dreaming Of Home

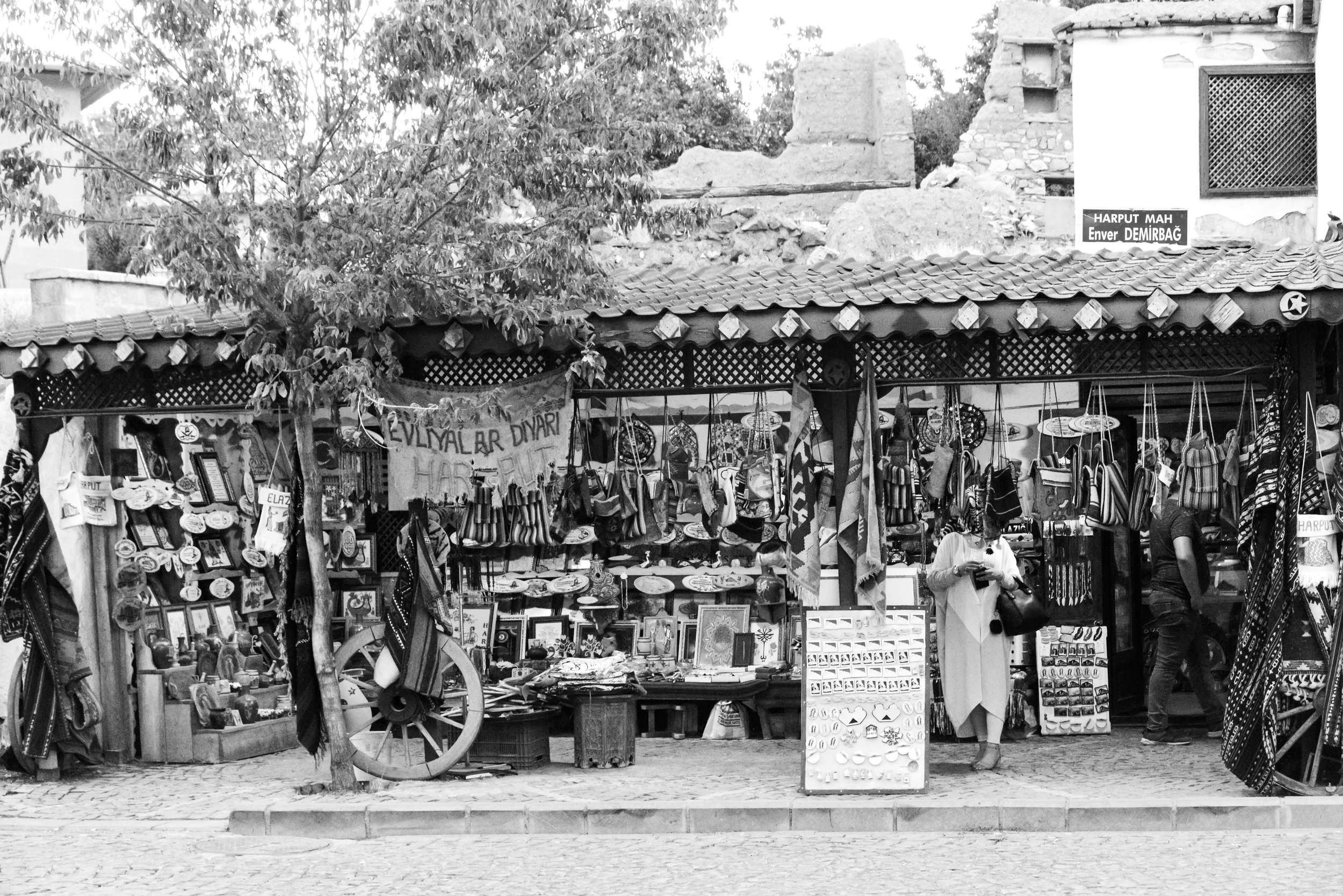

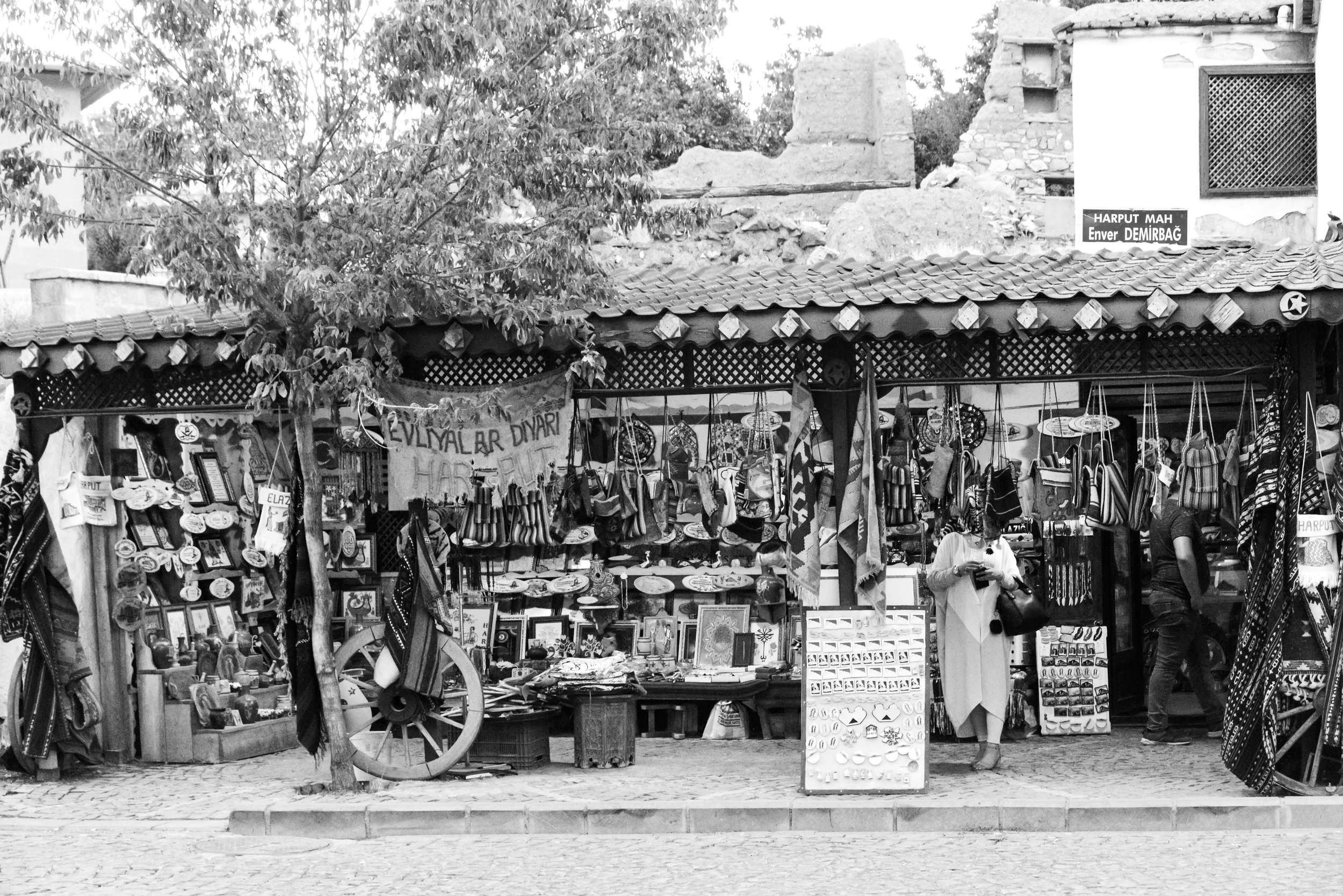

“The first thing I saw when we drove into Keban was a light brown, mud-brick ruin of a house. The house was on a slope overlooking the mountain road. The front wall was still intact, and its doorway, window and roof were open to the elements. I could imagine it as the house my family fled during the Hamidian Massacres. But then again, it could have been a much more recent house, abandoned simply to build a new one. Our house may have been burned down by the mobs, like so many other Armenian houses.”

from “Our Land: Finding My Family’s Village in Western Armenia” by Araxie Cass for The Armenian Weekly

In Place Of You

Our village at the foot of the mountains

Name washed away along with the blood

Disappears from the map

After the massacre

More ours than before

Now that our blood has soaked the soil

Now that you carry our DNA

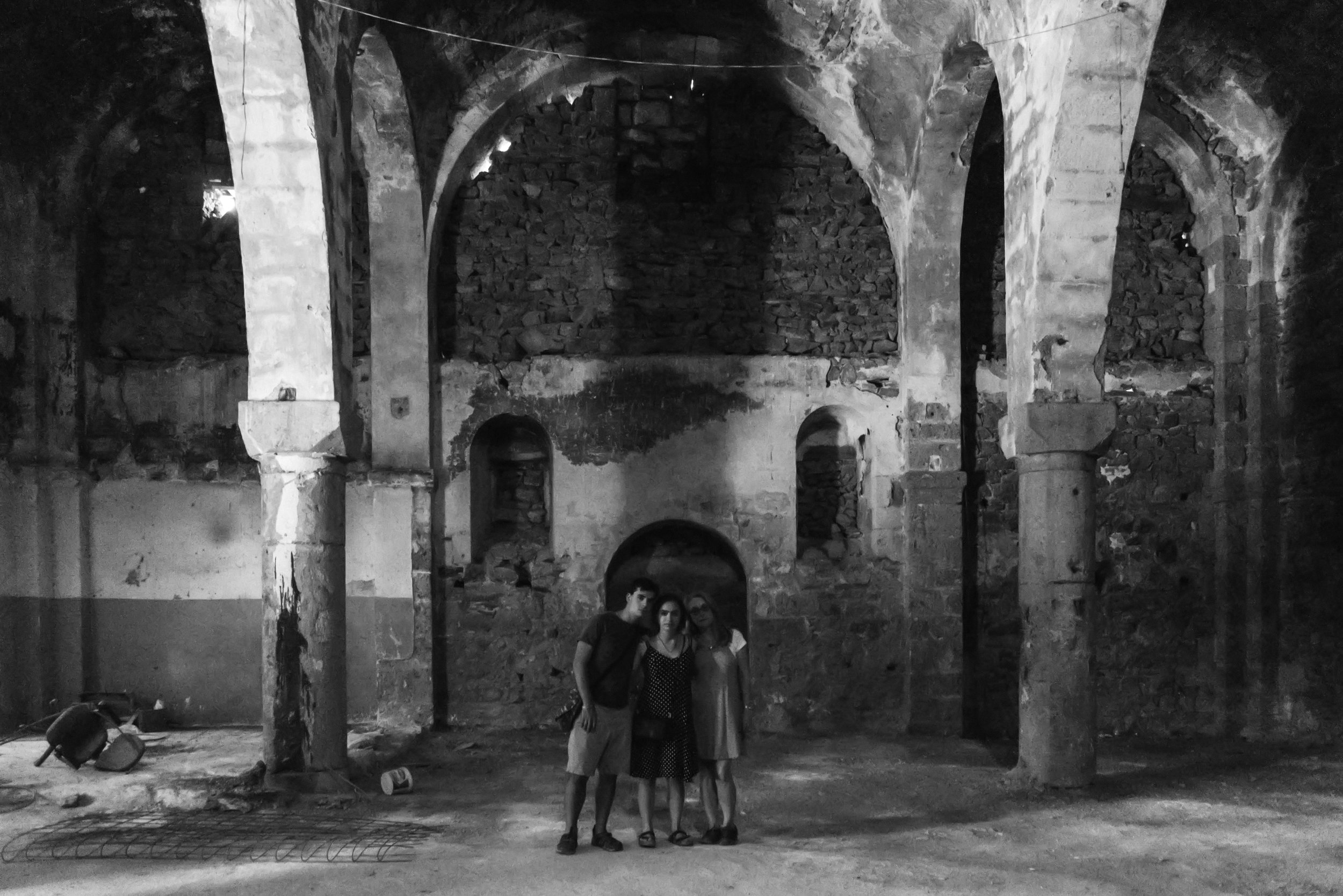

As You Remembered

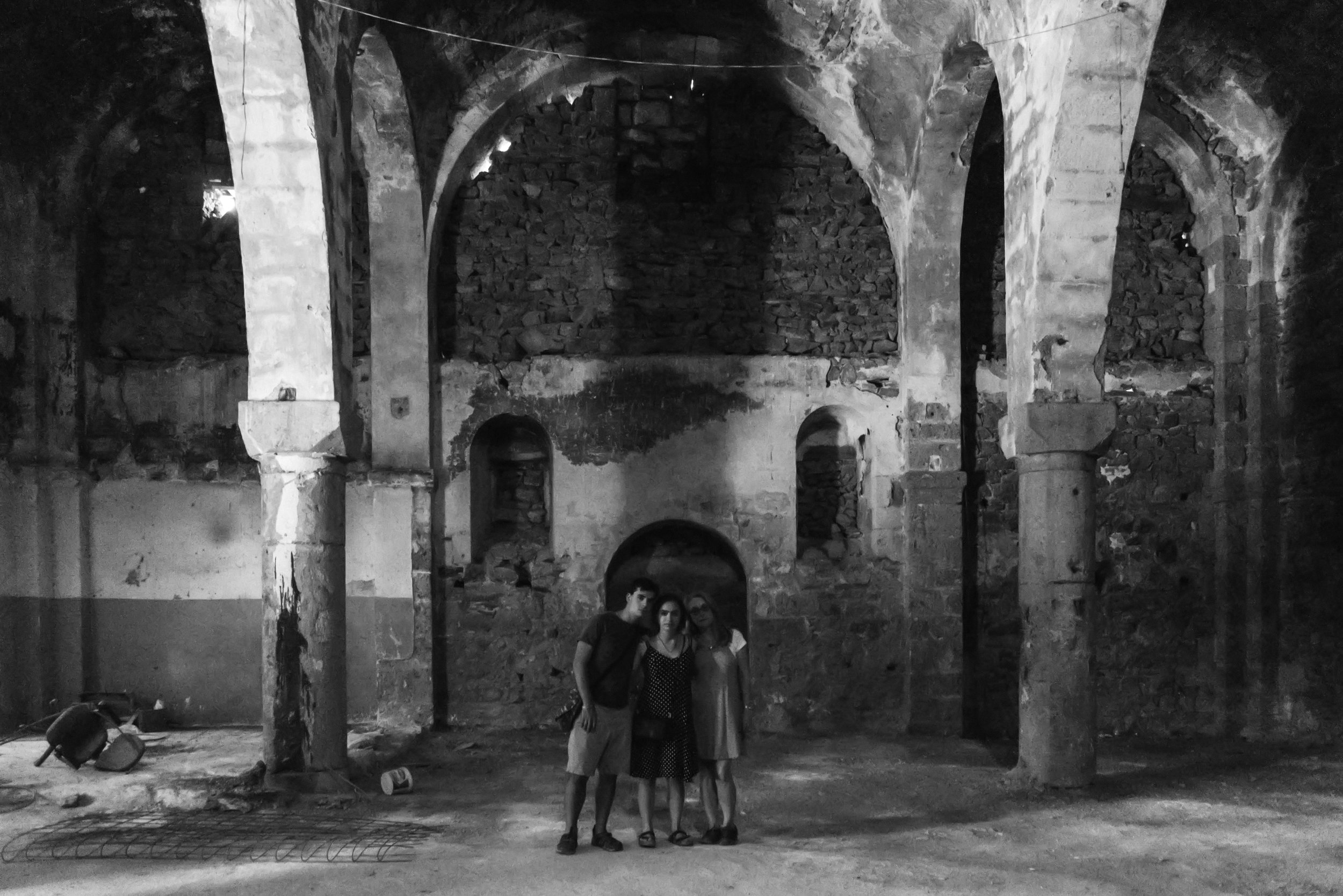

“I walked the streets of my grandmother’s stories, amazed to see them come to life before me. Wandering past village houses, I could see where some had been burned long ago and rebuilt with pieces scavenged from the ruins of other houses. The street of shops was just as Grandma described it, shopkeepers sitting in the shade of awnings in the heat of midday. But none of the people were our people and none could reply if I greeted them in our ancient tongue.”

from “Zaruhi” a short story by Kristin Anahit Cass

Our Houses Run Up the Hillside

The Day We Hid

“Ara’s eyes were glued to his little sister, but Suzanna knew what was

happening, so with a choking sob she gathered her resolve and ran. Ara felt himself

pulled behind her, and turned away.

They ran as fast as they could towards the orchard, their last hope. The soldier’s

shouts followed them as they ran into the trees, but years of hide and seek led them to a

little cave hidden by bushes and fallen tree branches.”

from “Good Friday” a short story by Araxie Cass

Sarkis Playing

Uncle Sarkis was a boy here, playing in these streets. During the Armenian Genocide he was conscripted into the army to care for wounded Turkish soldiers, after the Armenians had been stripped of their guns. At the end of World War I, the Armenians who had been conscripted for slave labor were forced to dig their own graves and then shot. But the little boy who played in the streets of our village and lived to witness the atrocities of the Genocide, escaped to live on in defiance.

The Mulberry Tree

The mulberry tree at my Grandma’s house shaded us on blistering days, gave us berries to snack on, and challenged us to attempt its towering height. I didn’t realize the significance of this tree to people exiled from Armenia until I returned there. Mulberries are everywhere in Armenia, delicious and wild, made into jam, oghi (a strong liquor), and home remedies for cold season. It was as if a piece of our homeland had risen up in front of my childhood home, shattering the sidewalk like our sacred Mount Ararat erupting.

To Deny

Colonized

“Sometimes between the shouting and the silence I could hear her speaking to me. “We the survivors of genocide, trauma is the inheritance of our descendants. Violence and secrets. Seeking to forget, we cannot forget. Our ancestral lands colonized and stolen, we were raped, trafficked and murdered. Those who survived were scattered in a global diaspora, cut off from their history and identity. Their secrets we struggled to keep until all who knew were dead, and only the aftermath of trauma remained. Their legacy is the inheritance of our children, until all that is left is the destruction handed down to them and they never knew the source of all they suffered.”

“We can’t speak of it, what they did to you. We must speak of it.”

from “Zaruhi” a short story by Kristin Anahit Cass

And We Burned Like the Timbers of Our Homes

“I imagine the family hiding in the hills, peering over bushes, watching their house go up in flames. But then again, their house could have been one of the many still standing, painted beige or pink, with a Kurdish family resettled inside.”

from “Our Land: Finding My Family’s Village in Western Armenia” by Araxie Cass for The Armenian Weekly

Մեր Տուն We Have a Home of Family Legend

“My family has a home of family legend, a two-story house with sleeping porches for hot summer nights, a tonir dug into the ground, and rugs on every floor. Nobody knows what happened to our family in the massacres, except that they lost their house, all of their possessions, and their youngest child, and that they fled from Gumish Madan to Kharberd, thinking they could find safety in a bigger urban center.”

from “Our Land: Finding My Family’s Village in Western Armenia” by Araxie Cass for The Armenian Weekly

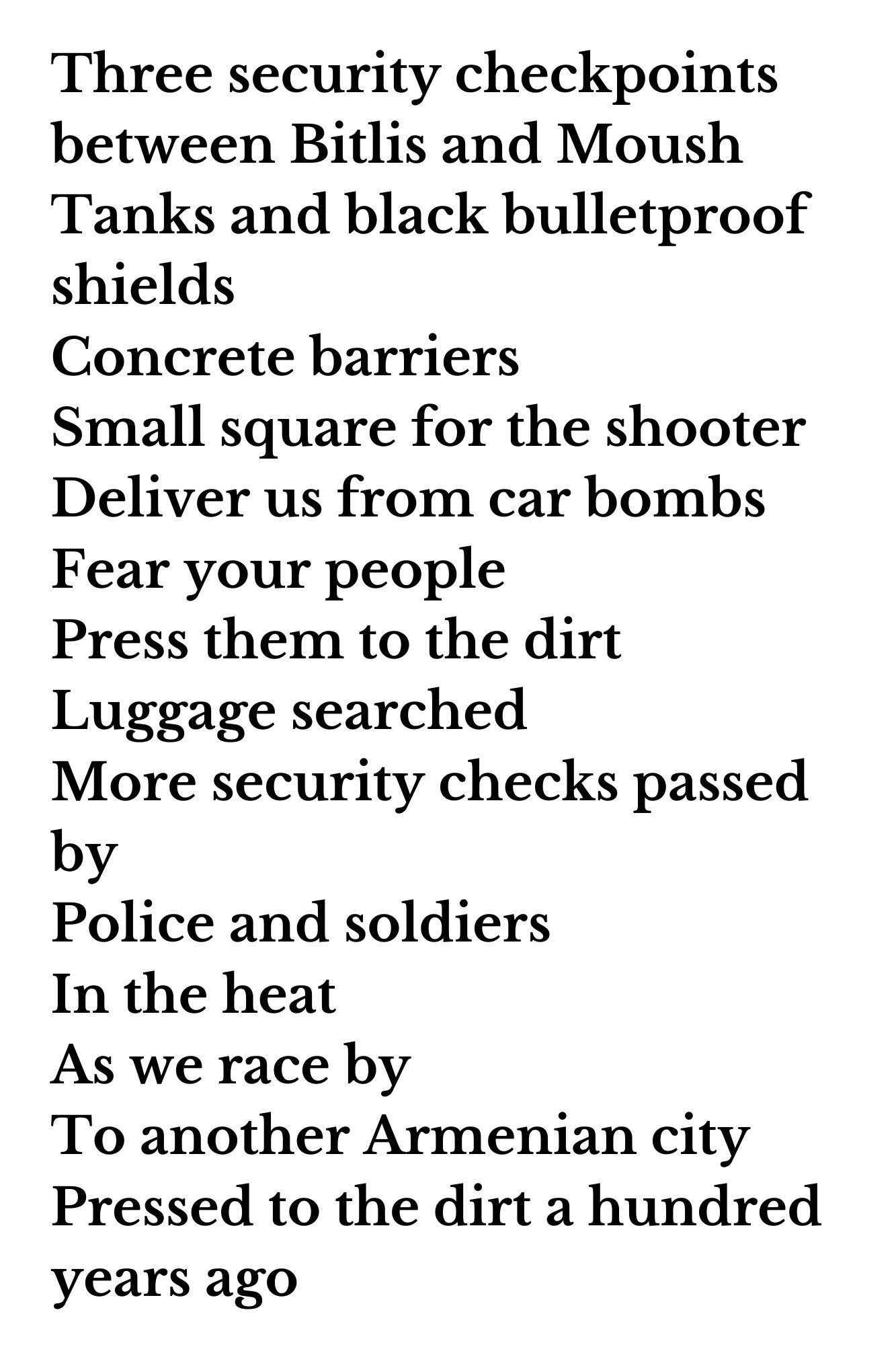

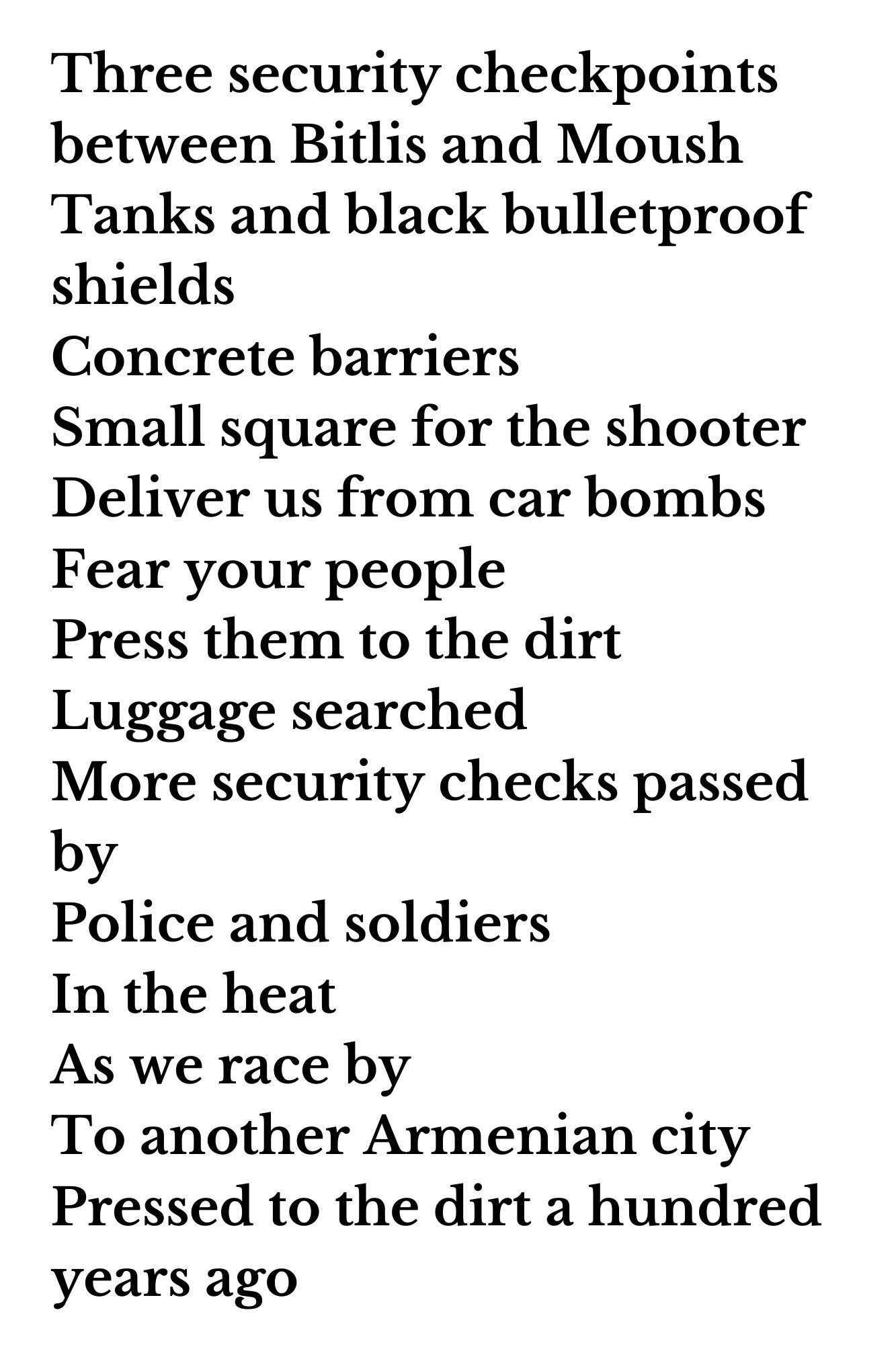

Sacred Spaces

“I didn’t expect to find the church. Most of the churches I saw going through the mountains were merely rubble. Walking towards the community buildings at the bottom of the hill, I saw a blackened stone building in a distinctive domed style. Walking around it, I saw the place where long ago someone had tried to hack off the cross motif, but found the stone too hard to obliterate. The doors were padlocked. I began to cry. A man came from the municipal building with huge iron keys on a ring. He went to the doors, opened them and gestured for me to go inside. Zaruhi, come with me. Today we will enter without fear.”

from “Zaruhi” a short story by Kristin Anahit Cass

They Discuss Our Return

The men are speaking about us. The last Armenians died two years ago, they say. Too bad you didn’t come sooner. What must that have been like, living in your homeland under a government that has been trying to annihilate your kind for a century? They explain that the village wants to preserve the Armenian church as a museum. It is the only way the government will not stand in the way of preservation.

Every Day I Resist Eradication

“Inside the church was empty. On the blackened walls there remained traces of the paintings, the blue of a holy gown, gold of a halo, traces of red, letters from our alphabet. Light streamed in through the oculus, filtered through the filthy windows. The air was cool, defying the flames that once consumed all herein. The silence that descended was peaceful, meditative. Yes, this is a sacred place. More than one hundred years had passed, and now I stood in a place I never expected to be. I had no words in that moment, only tears. Thank you, kind strangers who led me home. Who led us home.”

from “Zaruhi” a short story by Kristin Anahit Cass

I Wake Up Screaming

Ruined Kharberd

The government has interred itself in denial, and reparations are not even discussed. To offer reparations is to first put yourself in the place of those who suffered. And then to turn everything that you know inside out. What, then, is your national identity? What is the truth of the history you’ve been taught? What is your place in the world, and your country’s place? Who are you, really?

Memento Mori

My Family As Ghosts

Our lost homeland is a transitional place, a doorway. Those who died are forever interred there, a spiritual presence. Those who lived walked through that doorway into another world and lived with the ghosts of those who remained behind. And in the present, all the horrific violence that tore us from our land created a new country resting forever on the foundation of that violence. So that foundational violence reverberates through the generations for us Armenians and for Turks, the victims and the perpetrators.

And for me that is the continuing relevance of our loss, because now as an American I have inherited both the intergenerational trauma of my ethnic group and the foundational violence of the United States. And the cycle repeats itself as it has throughout history. So I envisage an imaginary republic where Turks did not commit genocide and ethnic cleansing. It is a place where our shared cultures combine to create something unique and wonderful.

Return

And I said to my daughter, as we walked, “Imagine what it would have been like if the Turkish government hadn’t committed genocide. It could be like…the Republic of Anatolia, with Turks and Armenians and Kurds and Greeks and Yazidis all living together. Just imagine what an amazing culture we could have had.”